菲律賓 Philippines

菲律賓 Philippines

Agriculture and Economic Recovery

The economy is breaking out of recession. It is hard to believe that since GDP in the first quarter contracted by 4.2%. Just the same, the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) and the Department of Finance (DOF) are optimistic based on economic indicators. The unemployment rate in March fell from 8.8% to 7.1% in just a month. The underemployment rate was down two percentage points also in March, to 16.2%. Labor force participation rate rose as well. According to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the economy had a net new employment in the first quarter of 2.8 million jobs.

Recovery this year is also hard to believe because of the lingering effect of COVID-19. The positive quarterly growth expected by our economic managers might just evaporate in the face of the second wave of COVID-19’s new cases starting in the second half of March this year. Health authorities once again had to be the killjoy to the economic recovery. They placed NCR Plus areas under ECQ and MECQ — the two strictest quarantine levels — in most of the second quarter. And when the surge in the NCR seemed to have been brought under control, new cases spiked in other parts of the country.

The good news we now have is that this year we have access to the COVID-19 vaccines. The uncertainty and desperation which gripped us last year are slowly being replaced with hope of reducing COVID-19 to a manageable disease, getting the economy to generate jobs and incomes, and of seizing back the normal lives we used to have before the pandemic snatched those from us in the first quarter of last year. The authorities will increasingly do an even better and faster job of vaccinating the population to attain herd immunity, hopefully this year.

With reasonable hope, the economy may grow for three straight quarters this year despite the current wave of new COVID-19 cases. Economic managers had set their eyes on economic growth from 6-7% this year. However, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), noting the slow pace of economic recovery, downgraded its projected economic growth of the Philippines to 5.4% from nearly 7%.

Just the same, analysts take such forecasts with a grain of salt. No one knows the future exactly. Economic managers could hit their economic growth target if better things happen in the economy in the second half of this year that forecasters failed to put into their economic forecasting models. Equally possible, growth could even be lower than the IMF’s projection.

We can define economic performance in the remaining quarters of the year the way we want it to be. It would be disappointing if we closed the year with an economic contraction, and if that happens, we deserve the hardships which that entails for not doing our part in rebuilding the economy from the recession.

I recall former NEDA Secretary and now Philippine Competition Commission Chairman Arsenio Balisacan telling a few of us that he told the Asian Development Bank (ADB) forecasters, who had always forecast the Philippines to be among the worst performers in Asia, to check their data and forecasting model they used. The ADB analysts had claimed that the projections they made were all based on existing data. That was in 2011, if I am not mistaken. Balisacan knew there were better developments in the economy and expected it to rebound.

Balisacan was right. Starting in 2012, the economy started to grow faster until it became the second-best performer in the ADB region after China. It stayed so even beyond the Aquino government, so much so that the NEDA had targeted to get rid of poverty in the country by 2040.

But of course, COVID-19 spoiled our chance of becoming a higher income developing country, and, like Malaysia, of significantly alleviating our poverty problem. All countries had their share of the global economic recession from COVID-19. The Philippine economy nosedived to double digit negative growth in the second quarter of 2020, to finish off that year with -9.5%.

AGRICULTURE’S CONTRIBUTION

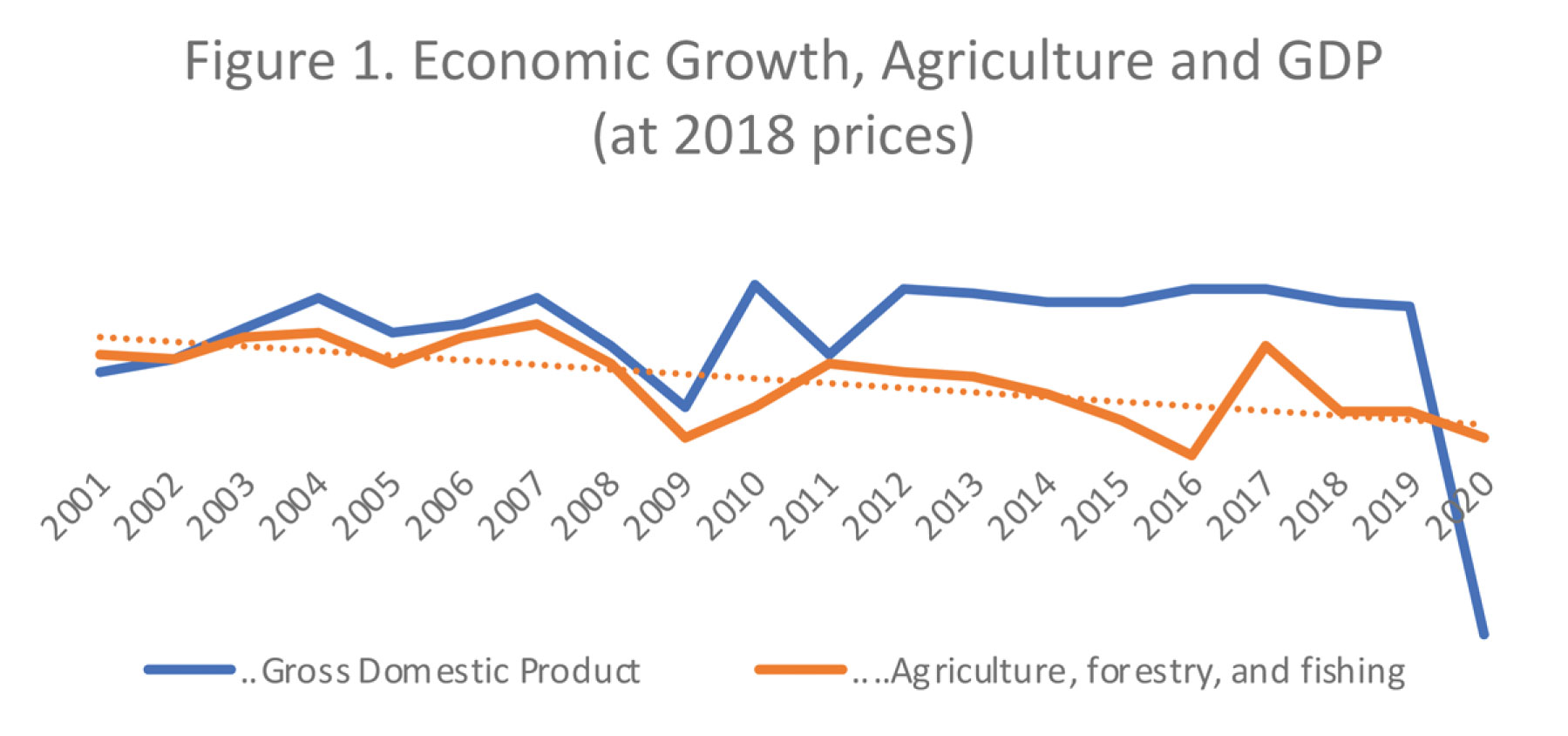

There are many things we can do to rebuild our economy better. I would just like to focus on agriculture. I examined agriculture’s performance since 2000. Over the past two decades, its growth had significantly dropped. Figure 1 shows how the growth of value added from agriculture, fisheries, and forestry has been going down since 2000. In the last decade, the disparity between GDP (gross domestic product) and GVA (gross value added) growth had widened, when the economy had become one of Asia’s best performers.

Agricultural growth failed to contribute to the higher growth of the economy. The resurgence of manufacturing and continued growth of the services sectors in the last decade failed to pull up agriculture’s performance. The average growth of GVA was 3.5% from 2001 to 2010 and fell to 1.9% in the last decade, excluding the COVID-19 year of 2020. In contrast, GDP expanded from an average growth of 5% in the earlier decade to 6.3% from 2011 to 2019.

If agriculture is going to make a significant contribution to economic recovery, it should recover its growth performance of several years back. But what should authorities focus on to realize that?

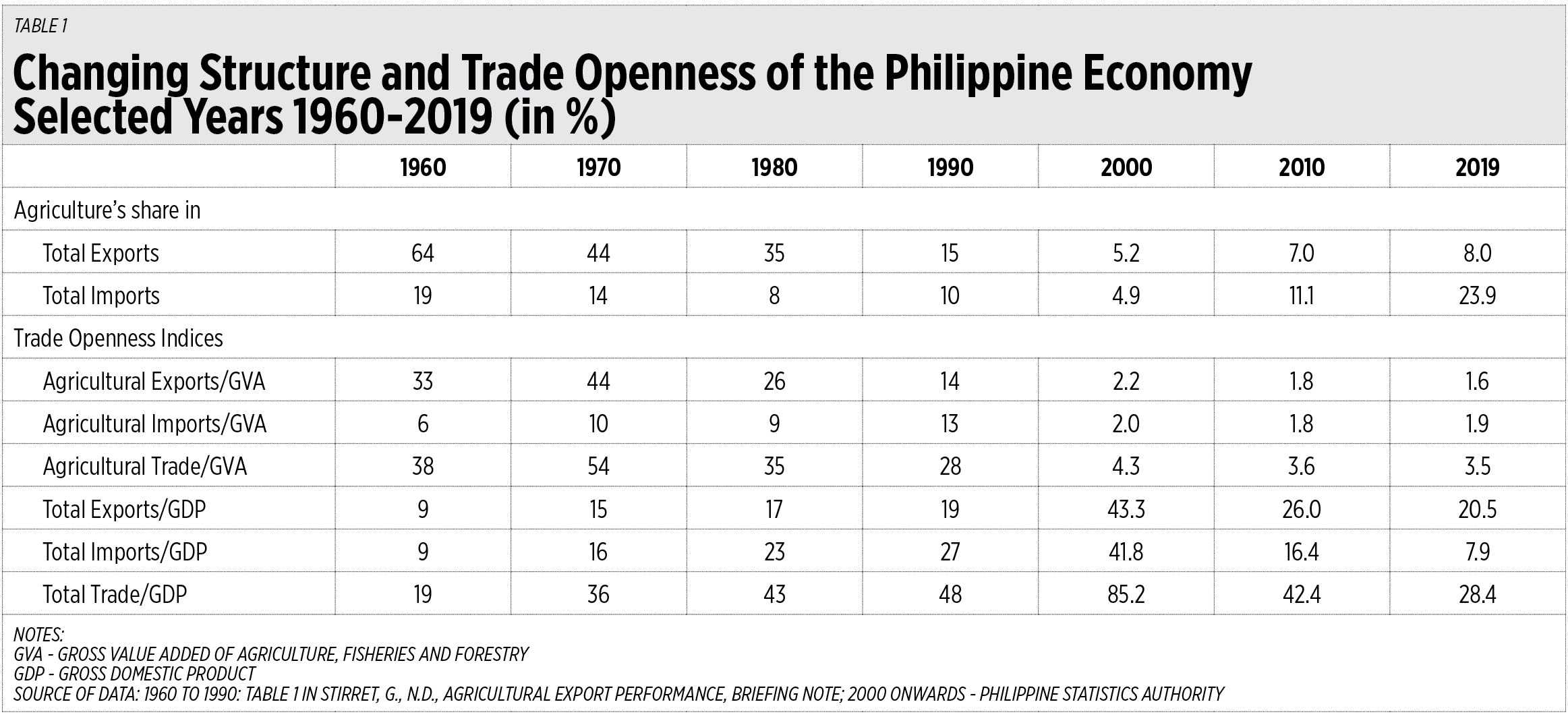

I associate this lackluster growth of agriculture to the falling tradability of the sector. Countries that tend to be more open to trade are those that are likely to succeed not only in increasing their agricultural exports, but also in garnering positive net exports. But progressively, our agriculture sector had increasing lost its capability to export and import through the years.

In Table 1, agriculture’s share in total exports used to be 64% in the 1960s. Two years ago, it had fallen to only 8%. It’s true we now have a more diversified export basket compared to the 1960s. Let us look at another indicator, agricultural exports share in gross value added of the sector. In the 1960s, that used to be a third and dropped to only 1.6% in 2019.

Declining tradability is reflected as well in agricultural and food imports. The share of agricultural imports to the total had declined until 2000. But in the most recent two decades, agriculture’s share to total imports climbed up because of rice imports. The National Food Authority (NFA) miscalculated its response to the 2008 rice crisis, and, in a panic, imported more rice than the country needed. In 2019, Congress enacted the rice tariffication law, liberalizing rice imports.

Falling importability of agriculture is better reflected in the share of imports to gross value added in agriculture. In the 1960s, that share was 6%. In the next three decades, it climbed up, reflecting falling productivity of the rice industry relative to food needs. Despite increases in rice imports in the last two decades, importability of the sector fell to less than 2%.

Summing it up, agricultural trade in proportion to GVA fell from 38% in the 1960s to only 3.5%. I associate this to falling sectoral growth, which I earlier noted. If the sector could recover its growth performance and contribute to a stronger and faster economic recovery, it has to become more open like the rest of the economy.

Source from: Ramon L. Clarete(2021). Agriculture and Economic Recovery. Retrieved from: Business World, Editors' Picks (June 20, 2021). https://www.bworldonline.com/agriculture-and-economic-recovery/